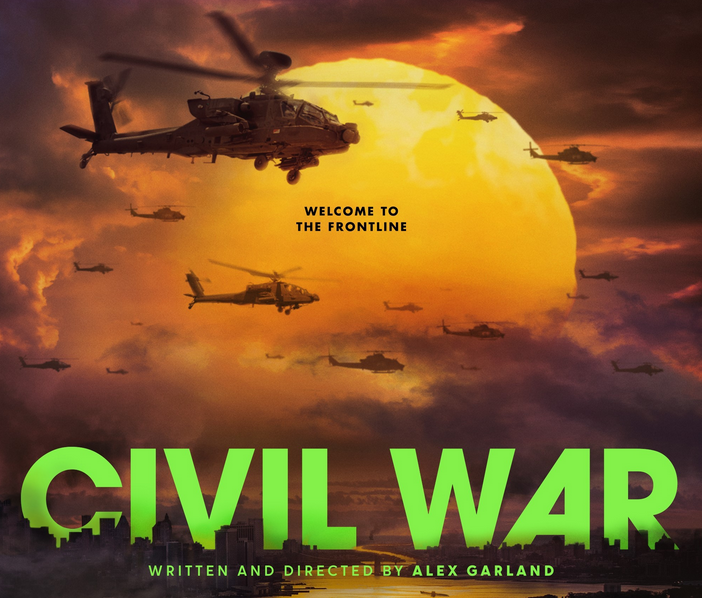

Civil War Review: Does It Actually Mean Anything?

Civil War is a beautifully shot miss, nicking the target before zinging off into the brush.

Director Alex Garland saw the blow to America during the 2020 political catastrophe and knew which way the wind could blow. His film is clearly intended as both a criticism and a warning: it can happen here, and you don’t want it to. But, while his film covers remarkable ground through deft use of visuals and sound, it only once skims close to real commentary on the state of this country and the reasons why such a horrific future could come to pass.

Warning, spoilers ahead.

The story is set in a dystopian near future, where the United States is embroiled in a civil war, with an authoritarian government facing off against secessionist movements. Amidst this turmoil, Lee Smith, a seasoned war photographer, rescues Jessie, an aspiring photojournalist, from a deadly suicide bombing in New York City. As tensions escalate, Lee, along with her colleague Joel, decides to undertake a perilous journey to Washington, D.C. to capture images and interview the controversial president, who is defying the 22nd Amendment by serving a third term. Their plans are further complicated when their mentor, Sammy, requests to join them up to Charlottesville, where forces from secessionist states are gathering. Unbeknownst to Lee, Jessie also persuades Joel to allow her to accompany them, providing the core cast of the drama to come.

The journey quickly spirals into a harrowing documentation of the war’s brutal realities. At a rural gas station, Jessie encounters a violent scene of two men being tortured under the guise of punishment for looting, and Lee manages to deescalate the tension by photographing the perpetrators. The group later witnesses and documents soldiers storming a building, and Jessie begins to find her stride as a war photographer under Lee’s mentorship. As they move deeper into conflict zones, encountering sniper battles and refugee camps, the relationships within the group are tested by the constant danger and moral dilemmas of wartime reporting. Tragically, as they reach Charlottesville and follow the advancing secessionist forces into a vulnerable Washington, D.C., Lee is killed in a shootout while trying to protect Jessie, who captures the chaotic moments leading up to the President’s execution, culminating in a final symbolic photograph that marks a pivotal moment in the conflict.

The moment when the film touches something real is during a confrontation with soldiers in a rural town outside Washington D.C. The protagonists have relocated Jessie, who ended up in the vehicle of another group of reporters: Tony and Bohai. They’re at the side of a mass grave being presided over by soldiers (as with many soldiers in this film, there isn’t necessarily clarity about which “side” of the fight they’re on. As Lee and the others go to intervene, a soldier in pink glasses shoots Bohai without warning and then proceeds to questions the others about their place of birth. The tension quivers as it becomes immediately clear the wrong answer equals a swift bullet (and that even the “right” answer isn’t going to get them out of there alive). So, by the time Tony answers, “Hong Kong,” we already know what’s coming.

“Oh, China?” says the pink-glasses soldier right before he pulls the trigger.

At this moment, we finally see absolute proof of what kind of America the unnamed President is presiding over: racist and filled with hate. While earlier lines about Gaddafi and bombing civilians gave us some context, these are remote, questionable: they’re stage-setters, not evidentiary moments. A mass grave filled with the bodies of men, women, and children paints about as clear a picture as it comes. These soldiers are evil, no matter whose side they’re on.

This line of racism and pure hatred is what I wish the film had opened itself to more. We have this scene and some scattered sidelong moments that suggest the reasons for the war engulfing this dark mirror America, but not enough of them. For this film to have real power, it needed to actually point to the clear ideologies behind the unnamed President’s regime of terror. Racism, sexism, xenophobia, religious fundamentalism: these are the enemies that give rise to vicious fruits like the pink-glasses soldier and his mass graves.

Overall, the audience received a shadowy experience from Civil War: warnings and criticisms without any suggestions for the future. Not only is this dangerously unnecessary in the current political climate, it also happens to be bad sci-fi.

A good science fiction film worldbuilds. In the classic era of pulp science fiction, it might have been enough to create pure contextual stories. But for something like this, the background realism matters as much as the moment-to-moment plot. And I’ve seen films handle this sort of thing deftly. Background characters, news broadcasts, one-liners that come with a weight of meaning: it’s possible to add reams of context to build the background world of a film. Only, Garland rarely seemed to take the opportunity to do so. Instead, we got lots of beautifully executed scenes of murder and mayhem against a clean backdrop. Why, for instance, are Texas and California allies in this film? Why is the war playing out as it does? We get the sense, while watching, that the answer to these questions is: “Because that’s what the script says happens.” I’m all for “speed of plot” solutions when needed, but not when they comprise the entire script.

Now, Garland certainly aimed at this neutral setting intentionally. The “it could happen anywhere” vibe of this film is strong, and I almost think it works in places. Nick Offerman highlighted this during an interview, too, saying that the director wanted to avoid providing a gemological trace of how the conflict in Civil War came to be: “One side or the other would get mad and say, ‘This is propaganda for him or for him or for her.’ And instead the movie disallows that, and if you’re able to silence the pundits in your head, and take it in as a work of art, then you receive it just as a citizen of humanity, and not of any political faction.”

But, in that, I cannot help but feel the same distance that often comes from real media coverage of these events in other parts of the world. There’s pretty much always a context to why people are fighting. There’s depth. Perhaps, someone could argue that such sci-fi worldbuilding isn’t the point of the film, but I would argue that the fear which brought Civil War into being is too important not to highlight the road that leads us there.

Matt Zoller Seitz, over at RogerEbert.com, has a great review that I think tackles the film from a useful angle. Seitz catches onto the lackluster character building as a feature rather than a bug. He writes that Civil War…

“is a portrait of the mentality of pure reporters, the types of people who are less interested in explaining what things “mean” (in the manner of an editorial writer or “pundit”) than in getting the scoop before the competition, by any means necessary. Whether the scoop takes the form of a written story, a TV news segment, or a still photo that wins a Pulitzer, the quest for the scoop is an end unto itself, and it’s bound up with the massive dopamine hit that that comes from putting oneself in harm’s way.”

In this, I think he’s put his finger on something useful. He gives too much credit, though, to the few moments of the film that grant us a suggestion of why horror takes place. As a critique of the both-sides-ism that major, corporate-owned liberal media has taken to providing as its bread-and butter, Civil War has some merit. As a critique of journalistic practices that separate the observer from the action, it has some merit. But, ultimately, it just doesn’t have enough punch to make this thesis stick. Maybe it would have in 2020, when Garland first conceived it, but I think that real-world conversations have run a bit faster than the studio production cycle.

Now, there are numerous areas where the film does succeed. For one thing, it does manage to avoid becoming a military-footage-fest, which was something I wondered about from the trailer. The trailer naturally chose to give us as many “money shots” of famous landmarks being blown up as possible. Seeing it, I’d asked myself: will this just be some sort of Army recruitment video writ long? That isn’t Garland’s vibe, but you never know.

I think the answer to that is a relative no (and I’ll explain why it’s relative in a moment).

None of the soldiers we see in this film are people who care: they’re all willing to kill or be killed, to murder anyone (especially the helpless) and take great joy in the experience. This may be accurate. We know the real-world stories of soldiers laughing as they gun targets down from helicopter vantage points, or jeering as they unload a tank’s main cannon to the chords of heavy metal. The terrors and cruelties of war are savage, and no “side” gets to come out smelling of roses.

The film’s final moment is a particularly well-done moment of this, as the victorious Western Forces kneel with shit-eating grins over the body of the President they’ve executed. It’s hard to feel any sense of victory at that moment, just another example of humans doing the worst things humans like to do.

But, I said that the film avoided being a recruitment video only in relative terms, and I want to come back to that.

Any film that provides heart-pounding explosions, gun fights, and military maneuvers is a risky piece in the indoctrination of its viewers to warfare glorification. The photo-snap pauses of horrific moments were not enough to startle many viewers out of their apathy or their interest: we simply didn’t get enough of the sheer pointlessness of the battles. Instead, we got realistically executed combat scenes as soldiers storm the wall-surrounded White House. That’s been done enough times in recent cinema history to seem a bit masturbatory, and I found myself less immersed in the film’s message than bored with the ceaseless slaughter of the hapless Secret Service people.

Perhaps the largest issue with Civil War, however, is its lack of character building. It relies on the work of its superb acting ensemble to carry the day — and they certainly do. With a different cast, I don’t know if this would have worked even as well as it did. Kirsten Dunst looks haggard and weary in an absolutely believable way, and Stephen McKinley Henderson’s performance was exemplary. Nick Offerman likewise provided a stellar, if brief, performance as the unnamed President. The subtlety of facial expression and vocal inflection Nick provided was superb.

However, for all that these actors, and the rest of the cast, bring to the film, I just found myself wondering, “Why should I care?” It’s not so much that they’re unlikable as a protagonist group, it’s just that they’re a bit boring.

Don’t get me wrong: I think the film, overall, is more of a success than it is a failure. It is gorgeously shot, its sound-design really requires a full movie theater to be appreciated for the work of art it is; the acting is stellar and the pacing of the script is crisp. Furthermore, it is certain to surprise those viewers who were expecting a fully patriotic, pro-military, yay-to-war, gun-fest. But Civil War, at least for me, still misses the beat.

One doesn’t need to tackle specific political talking points to showcase when something is wrong. If the film had been a bit less wary of arousing the partisan fervor it portrays, it might have offered the impact needed to help foment some change.